US retailer Zappos offers new employees a bonus equivalent to one month's salary at the end of their onboarding process to leave the organisation. Amazon goes the extra mile, offering all permanent employees up to $5000 annually to pack their things1. But why?

Offering a bonus for leaving the organisation encourages staff turnover among unmotivated employees. Both Zappos and Amazon are convinced that it pays in the long run to say goodbye to relatively underperforming employees in order to keep a strong team. And that idea is not out of the blue. Research shows that there is an optimal attrition rate.

But what exactly is staff turnover? How can you optimise staff management to pursue the right attrition rate? And what costs are involved after staff turnover?

Employee turnover definition

Employee turnover refers to employees who leave an employer, either voluntarily or compulsorily, through dissolution of the employment contract. Staff turnover can be divided into two categories: desired and undesired staff turnover. In case of low performance and little tangible knowledge, there is desired (functional) staff turnover. In the case of high performance and a lot of knowledge that is difficult to transfer, it can be said that there is undesired (dysfunctional) staff turnover2.

So, in the examples of Zappos and Amazon, they are trying to encourage desirable employee turnover. This article further explains the distinction between these types of employee turnover. It also provides guidance on how to determine the ideal attrition rate.

Calculate staff turnover

Attrition can be calculated by dividing the number of outgoing employees by the total workforce. This is often expressed in the form of an attrition rate. The total workforce is calculated including the departed employees. For example, if 42 employees have left the organisation from a total of 500 employees, this can be expressed as an outflow percentage of 42/500*100 = 8.4%.

Undesirable staff turnover

The risk of losing high-performing employees raises concerns for many organisations. For example: Employee A of a sales department within any organisation is very successful and manages to retain key customers. The sales employee has a lot of product and sales knowledge, is well-liked, never ill, highly profitable and has thus developed into a key pillar within the organisation. What happens when this employee leaves the organisation? In the short term, costs arise. A new vacancy has to be put out, replacement has to be arranged, knowledge transfer, administration handling, conducting exit interview, induction process, etc. But in the above example, the biggest pain is felt mainly in the long term. The department is under pressure and similar results will not be achieved in the coming months. In the worst case, this can lead to demotivation, absenteeism and even more unwanted turnover.

In summary, in the case of unwanted turnover, the costs can be quite high, especially when one only has a short-term view. Strategic personnel management is therefore essential. HR departments should distinguish themselves in this more often by systematically providing insight into such staff turnover. Think about: Where are risks? How can we better bind and keep employees interested? What are the reasons for turnover? What can we do about it?

Desired staff turnover

As explained earlier, within desirable staff turnover, one loses employees with relatively little (tacit) knowledge. Also, the employee performs (below) average. So there is no loss of important assets or resources that add significant value to the organisation. The costs within this category are therefore mainly limited to the short term. On the contrary, in the long term gains can be made after departure.

Contrary to what some human resources officers think, knowing triggers that lead to desired employee turnover offers great profit potential. After all, organisations that do not have to cough up inflow-related costs each time are more effective.

Dealing with staff turnover

So there is a big difference between desirable and undesirable attrition. But what can we do with this distinction? And to what extent can we influence staff turnover?

First of all, only one outflow rate is often reported. No distinction is made here between desired and undesired staff turnover. Strange, because combining these categories does not really give a good picture at all. A first tip is therefore to scrutinise both the figures for desired and undesired turnover separately. This is the only way to determine whether there is either too much unwanted turnover or too little desired turnover.

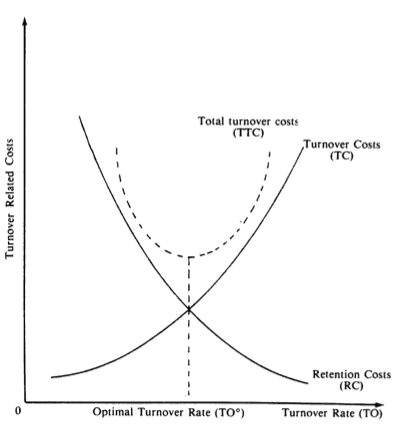

The second step is to determine the optimal attrition rate within your organisation. In some cases, an overall attrition rate of 30 per cent is nothing to worry about. At Google, for example, the average length of employment is only 1.1 years3. In other organisations, such a high attrition rate would be disastrous. So how do you know what the right attrition rate is for your organisation? As with many other things, it's all about a healthy balance sheet. However now literally, in a financial sense. This balance sheet is shown below4.

The optimal rate lies exactly at the intersection of attrition and retention costs. That sounds nice, but how can this be calculated? What exactly are attrition costs and even more difficult, what are retention costs?

Running costs

A good start is to identify costs that are objectively measurable. For example, what does putting out an ad cost? How many hours does one spend on job interviews? How much time do exit interviews cost?

Next, it is important to consider how long it takes to bring a new employee up to the level of the departed employee. If there is unwanted turnover, this will take more time than with desired turnover. What is the cost of this process? More importantly, what is the profit lost during the period when the employee is not yet at that level?

Objective retention costs

Regarding costs of retention (retention costs), things get a bit more complicated. Yet here too, there are certainly costs that can be approached objectively. In any case, step one is to understand what matters to the employee within the terms of employment when deciding whether or not to stay with the organisation. In the primary area, for example, one can look at what providing perspective/growth costs. Here, calculate the difference between the absolute starting salary and the costs required annually for an employee to achieve growth to, say, a senior role. Salary scales often help to make this explicit.

Subjective retention costs

Understanding subjective drives is trickier. How do you find out what binds employees and what makes them stay captivated? Important to find out this information is an open culture combined with a systematic feedback system. Employees must feel the space to be able to give feedback, and be given the opportunity to do so.

Giving feedback does not come naturally in every organisation. When the organisational culture is closed, the step to give feedback in an evaluation interview, for example, can be a big one. Digital, anonymous feedback solutions offer a solution here. This way, employees can offer honest and open insight into such matters. A win-win situation, as feedback solutions also contribute to creating an open culture5. Unfortunately, the question is still too often whether managers are willing, daring and able to go along with this change.

Only when a solid feedback system is in place can one really map the full scope of drivers. Only then can retention costs be further specified and the best outflow percentage determined. One can thus focus more effectively on encouraging desirable staff turnover and preventing undesirable staff turnover. Perhaps then, offering compensation for leaving the organisation is not even necessary.

Want to gain data-based insights into departure and prevention reasons? Then read here More about us (EXperience) outflow survey.

Sources

- Umoh, R. (2018). Why Amazon pays employees $5,000 to quit. CNBC.

- Johnson, J. T., Griffeth, R. W., & Griffin, M. (2000). Factors discriminating functional and dysfunctional salesforce turnover. Journal of business & industrial marketing, 15(6), 399-415.

- Johnson, T. (2018). The Real Problem With Tech Professionals: High Turnover. Forbes.

- Abelson, M. A., & Baysinger, B. D. (1984). Optimal and dysfunctional turnover: Toward an organisational level model. Academy of management Review, 9(2), 331-341.

- Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T., & Grimes, J. M. (2010). Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: E-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies. Government information quarterly, 27(3), 264-271.