Influence of employee satisfaction on employee turnover

Year: 2014

Influence of employee satisfaction on employee turnoverIt was assumed that the combination between dissatisfaction with the work (employee satisfaction) and available alternatives leads to leaving an organisation (Mobley, 1977). There are a number of issues that have not been sufficiently addressed until then. One important one is that most theories have not paid attention to interrelationships, social pressure and commitment.

In addition, mechanisms of motivations are not described while this is of great importance (Maertz & Griffeth, 2004). In this paper, therefore, the role of employee satisfaction at staff turnover discussed.

Shocks to complement employee satisfaction

Knowledge of these shocks can be used to address dysfunctional staff turnover and gain long-term competitive advantages in human and social capital.

The extent of employee satisfaction is a factor but insufficient and too limited for it to be the dominant cause for staff turnover (Holtom et al., 2005). The Hom-Griffeth model (Hom & Griffeth, 1991) was one of the first models to observe that there are 'shocks'. Shocks are based on the external environment that can eventually lead to staff turnover. The eventual exit from the organisation takes place based on employee initiative. Due to this human-based approach, the organisation and stakeholders are external players that can cause both positive and negative shocks in employees (Holtom et al., 2005). Within this theory by Hom and Griffeth (1991), a negative or positive experience takes centre stage. Knowledge of these shocks can be used to identify dysfunctional staff turnover and gain long-term competitive advantages in terms of human and social capital (Becker, Huselid, & Ulrich, 2001; Pfeffer, 1995).

Knowledge-intensive organisations that pay attention to this are able to create competitive advantages, according to Becker et al. (2001). This makes it important for knowledge-intensive organisations to create an understanding of both employee satisfaction as shocks experienced by employees. The following page explains the principle of shocks.

Shocks and employee satisfaction

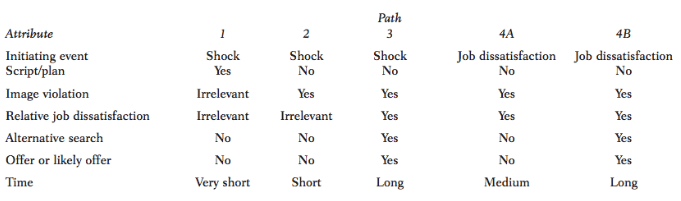

The shocks are divided into four standard patterns. These patterns play out in 90 per cent of staff turnover play a role and can therefore be classified in this model (Holtom, et al., 2005).

Pattern 1

An employee leaves the organisation without considering his current connections to the organisation and alternative positions. The degree of employee satisfaction is not relevant within this movement. An example is that the employee's partner for an interesting job abroad has found (shock) and the employee wants to move with him. The question is therefore whether the organisation could influence this.

Pattern 2

Staff turnover within this group is caused by shock. The shock leads to the revaluation of social connections within the organisation. This is explained by the impairment of an employee's value image. The employee then leaves the organisation without an alternative position. An example is when an employee is barred from promotion after which, after consideration, the employee decides to leave the organisation. Importantly, employee satisfaction about the work for shock can be high and, as a result, this is not a representative picture.

Pattern 3

A shock within this pattern leads to image damage between the employee and the organisation. The employee compares his current position with alternative positions outside the organisation. This may include an offered position. Despite employee satisfaction about the work, the employee may choose to leave the organisation.

Pattern 4 a/b

Lower employee satisfaction about work is within this group the cause of voluntary staff turnover. The employee becomes aware of job dissatisfaction and decides to leave the organisation.

Pattern one is, within the study, the pattern that occurs relatively frequently and predictably.

Within pattern three, 91 per cent of employees leave the organisation unexpectedly Holtom et al. (2005). This pattern is particularly prevalent within similar knowledge-intensive organisations such as accountancy firms. Within the study, pattern one is the pattern that occurs relatively frequently and predictably.

Eight forces model

To supplement missing factors in the literature alongside these shocks, a framework was used by Maertz and Griffeth (2004) within which explanation is given of what forces lead to conservation or staff turnover. In the framework, there are eight applicable forces that influence whether or not an employee leaves:

(1) Affective forces: this involves emotional state within the organisation. Poor emotional state leads to outflow or loss of commitment.

(2) Calculated forces: this is a rational force where the employee thinks rationally about the chances of achieving his important values and goals. Here, a negative outcome leads to staff turnover.

(3) Contractual forces: these forces focus on the assumed obligations in relation to the psychological contract. This depends on the assumed norm of reciprocity.

(4) Behavioural forces: This involves the will to reduce psychological costs by investing in participation within the organisation. Higher costs motivate investing in participation and lower costs do not. Thus, with lower costs, the employee is more likely to leave the organisation.

(5) Alternative forces: this is the extent and strength of its own effectiveness regarding obtaining alternative positions outside the organisation. High efficiency and effectiveness lead to staff turnover.

(6) Normative forces: meeting shared expectations outside the organisation. Assuming there is motivation to meet these external expectations affects staff turnover.

(7) Moral forces: these forces are based on the link between behaviour and values regarding staff turnover. This ranges from 'changing jobs often is good' to 'being loyal to an organisation is a virtue'.

(8) Binding forces: motivation to stay or leave an organisation depends on connectedness with immediate colleagues and other groups within the organisation. Connectedness with colleagues and other groups runs parallel to connectedness with the organisation.

Low employee satisfaction involves work, according to Maertz and Griffeth (2005), need not directly lead to staff turnover. Emotions are not in employee satisfaction included but play an important role, according to Maertz and Griffieth (2005). The aforementioned factors provide indicators for this to staff turnover estimate. An employee compares and values all strengths between the current and alternative organisation. Alternative positions (5) is a crucial factor in the process of leaving a knowledge-intensive organisation. When an employee does not have a good alternative, the binding forces (8) weigh more heavily against leaving the organisation (Lee & Mitchell, 1994). When there is an alternative, the employee will handle the consideration more rationally.

Embedding in function

Apart from the idea of shocks and the force model mentioned above, it staff turnover according to Mitchell, Holtom, Lee and Erez (2001), influenced by the degree of job embeddedness. This includes (1) connections with other employees, teams and groups, (2) perceptions of suitability for job, organisation and environment and (3) what an employee would give up when leaving the organisation (Mitchell et al., 2001). In this study, it was shown that job embeddedness is an important mediating variable among factors that influence the employee's eventual leaving. The three dimensions; connections, suitability and sacrifice have both an organisational and communal component.

Psychological contract

According to Guest (1998), the state of a psychological contract determines whether an employee eventually leaves the organisation. According to Rousseau (1989), a psychological contract is an individual's belief regarding the terms and conditions of an exchange agreement between the employee and the organisation. Organisational culture, HR policies, experience, expectations and alternatives are underlying factors, according to this theory. These factors determine the level of employee satisfaction, commitment, sense of security, relationships, motivation, et cetera. Due to the number of factors involved in the psychological contract, it is impossible to make it measurable (Freese, Schalk & Croon, 2008). In addition to this theory by Guest (1998), according to Khilji and Wang's (2006) research employee satisfaction about HR policies plays an important role. According to Ongori (2007), the probability of voluntary employee turnover is significantly higher among organisations with low satisfaction with HR services than those with better rated HR policies. Among younger employees, this effect is stronger than among older employees. Ongori (2007) summarises this in his literature review as poor implementation of HR policies, recruitment policies, management and lack of motivation.

Conclusion

There are several insights that explain the decision-making process of a departing employee. In thinking of shocks, there are four patterns an employee may go through before leaving. One pattern has the variable employee satisfaction as the main cause for leaving an organisation. The remaining three patterns assume one or more shocks. These can be either positive or negative and are categorised into factors such as alternative job(s), predetermined outflow, etc. An important fact, in the case of a shock, is that the pattern the employee follows is determined by the external environment.

Besides shocks, there are also forces that play a role in an employee's exit process. These are a total of eight forces; (1) Affective forces, (2) calculated forces, (3) contractual forces, (4) behavioural forces, (5) alternative forces, (6) normative forces, (7) moral forces and (8) binding forces. These forces are constantly assessed and compared with other organisations. If the other organisation then offers the (5) alternative forces a better future, the (8) binding forces will eventually lose out to the alternative forces.

Mitchell et al (2001) argues that employee turnover is explained by the degree of embeddedness within the job. Variables that explain this theory are (1) attachment to environment, (2) perception of job suitability and (3) what is given up when the employee leaves the organisation. Besides embeddedness, Guest (1998) mentions the psychological contract as an all-embracing basis. Here, organisational culture, HR policies, experience, expectations and alternatives are central as causes. The last explanation for leaving the organisation is that of Khilji and Wang (2006). They showed in their study that employee satisfaction with HR policies largely predicts voluntary employee turnover within organisations. Among younger employees, this effect is stronger.

Knowledge-intensive organisations: What are they and what role does knowledge management play?This article focuses on knowledge-intensive organisations. To create substantive consensus on knowledge-intensive organisations, a definition of the associated terms was first formulated. According to Sun (2010), an organisation can be defined as a movement that creates and maintains a social entity to achieve a certain goal. It is a structured, coordinated and purposeful social entity created and maintained by people.

Daft (2008) describes that these social entities are consciously designed as structured and coordinated systems connected to the external environment.

Introduction

This article is based on the thesis Unwanted voluntary staff turnover within knowledge-intensive organisations. This article answers the first sub-question of this thesis.

According to Tsoukas and Vladimirou (2001), knowledge is the individual capacity to make distinctions within work based on theory or context. Within organisations, this individual knowledge can be divided into tacit (intangible) and explicit (tangible) knowledge. Tacit knowledge refers to intangible knowledge, often held by individuals, while tangible knowledge, known as explicit knowledge, is mainly based on documented-and therefore easily transferable-knowledge (Choo & Bontis, 2002). As formulated in the problem statement, knowledge-intensive organisations are resource-based such that knowledge is a key resource.

Besides knowledge, employees contain skills and abilities that, together with knowledge, are categorised under human resources. These resources, including knowledge, are important for competitive advantage (Wright et al., 1994). Resource-based knowledge is therefore necessary to resell services or products of organisations (Sarvay, 1999).

Knowledge for competitive advantage

As shown, within knowledge-intensive organisations, human resources are the most important strategic asset and knowledge is an important part of such an organisation's business model (Choo & Bontis, 2002). This makes knowledge the most important part of the key resources of knowledge-intensive organisations. Priem and Butler (2001) call these key resources a prerequisite for competitive advantage within such organisations. Preservation of knowledge-based resources is therefore important to maintain competitive advantage.

Such organisations can respond to this through 'resource-based strategies' that focus on both retention and expansion of knowledge (Chaharbaghi & Lynch, 1999). According to Chaharbaghi and Lynch (1999), constant competitive advantage is based on both resource advantage and strategy advantage. This constant competitive advantage is known as sustainable competitive advantage.

The height of barriers determines how sustainable a competitive advantage is.

Sustainable competitive advantage, according to Oliver (1997), can be defined as the implementation of a value-creating strategy that is not susceptible to imitation and has not yet been applied by competitors. Porter (1985) states that sustainable competitive advantage depends on the height of barriers against imitation of key resources. The height of barriers determines how sustainable a competitive advantage is. An organisation with competitive knowledge advantage is able to extend competitive advantage (Oliver, 1997). This makes it important for knowledge-intensive organisations to maintain this knowledge advantage so that the competitive edge can be maintained and expanded.

Disadvantages of knowledge management

Many knowledge-intensive organisations, in order to maintain sustainable competitive advantage, use knowledge management at a strategic level. If it is assumed that knowledge contains data and information, knowledge management can be defined as management aimed at individuals to retrieve potentially useful information (Alavi & Leidner, 2001). According to Choo and Bontis (2002), the main context in which knowledge management finds itself is an organisation's strategy. When knowledge management involves knowledge that is so deeply rooted in routines and experience, it is likely to be unique and difficult to reproduce (Choo & Bontis, 2002).

Coding knowledge within these systems makes it less easy for competitors to imitate knowledge.

Within organisations such as McKinsey, IBM or HP, knowledge management, within the culture of the respective organisation, has developed organically (Sarvay, 2002). Coding knowledge within these systems makes it less easy for competitors to imitate knowledge. In contrast, this leads to poorer performance within the organisation. Performance is suppressed by procedures and systems and the amount of extra information that is not relevant to the work will further increase. Only when knowledge offers such an advantage that it cancels out costs due to coding does it make sense to apply knowledge coding (Schulz & Jobe, 2001).

Power shift to employees

Shifting from lifetime employment to lifetime employability, through social acceptance, bonding is a less certain factor (Forrier & Sels, 2003). They argue that lifetime employment is the ability by which an individual is able to perform various functions within the current labour market. The power in the labour market, due to unique skills, abilities and knowledge available to employees, shifts more strongly to the employee (Dibble, 1999). Employees within knowledge-intensive organisation are more likely to voluntarily leave (Forrier & Sels, 2003). This makes it important for organisations to avoid such impact as much as possible. To gain insight into motivations of these employees, the motivations of these employees were explained within sub-question two.

Conclusion

In conclusion, knowledge-intensive organisations rely on tacit knowledge held by highly skilled individuals. Coding this knowledge, and managing it through strategic knowledge management, are intensive and costly investments that do not necessarily offer positive results. Undesirable staff turnover with resource-based knowledge directly causes a worse competitive position in knowledge-intensive organisations.

The influence of job content on employee turnoverThanks to this weekly blog, we hope to learn more about the drivers around staff turnover and thereby provide new tools. This week, in the search for statistically proven reasons for employee turnover, we discuss the influence of job content. This study used a sample that includes 1000+ respondents.

How can staff turnover be explained?

Staff turnover can be explained from the thoughts that the 4As (job content, conditions, relationships and terms) influence the intention to leave the organisation. Each "A" is statistically (linearly) linked to actual perceptions of a career and, among other variables, the degree of voluntariness, gender, education level, etc.

What is labour content?

Labour content refers to the nature and level of work and how these tasks are to be performed. Important concerns within job content include task structure, autonomy, collaboration opportunities and qualification requirements.

Influence of work content

The data show that job expectations and the extent to which they match reality are the main determinants of whether someone leaves the organisation (p = < .05). Interestingly, expectations do not play a significant role in voluntary staff turnover. Possibly this problem "shifts" when only voluntary staff turnover is involved. The perception of job content itself (the whole concept of job content) affects in voluntary staff turnover well the perception of career (p = < .05).

Conclusion

The perception of job content factor clearly plays a significant role and is thus statistically determinant in a career of the employee in our sample. Content expectations play a role particularly in involuntary staff turnover. We consider this to be the most striking result. Evidently, the involuntary leaving employee experiences the content so intensely that it ultimately significantly influences the overall perception upon departure.

What is staff turnover?US retailer Zappos offers new employees a bonus equivalent to one month's salary at the end of their onboarding process to leave the organisation. Amazon goes the extra mile, offering all permanent employees up to $5000 annually to pack their things1. But why?

Offering a bonus for leaving the organisation encourages staff turnover among unmotivated employees. Both Zappos and Amazon are convinced that it pays in the long run to say goodbye to relatively underperforming employees in order to keep a strong team. And that idea is not out of the blue. Research shows that there is an optimal attrition rate.

But what exactly is staff turnover? How can you optimise staff management to pursue the right attrition rate? And what costs are involved after staff turnover?

Employee turnover definition

Employee turnover refers to employees who leave an employer, either voluntarily or compulsorily, through dissolution of the employment contract. Staff turnover can be divided into two categories: desired and undesired staff turnover. In case of low performance and little tangible knowledge, there is desired (functional) staff turnover. In the case of high performance and a lot of knowledge that is difficult to transfer, it can be said that there is undesired (dysfunctional) staff turnover2.

So, in the examples of Zappos and Amazon, they are trying to encourage desirable employee turnover. This article further explains the distinction between these types of employee turnover. It also provides guidance on how to determine the ideal attrition rate.

Calculate staff turnover

Attrition can be calculated by dividing the number of outgoing employees by the total workforce. This is often expressed in the form of an attrition rate. The total workforce is calculated including the departed employees. For example, if 42 employees have left the organisation from a total of 500 employees, this can be expressed as an outflow percentage of 42/500*100 = 8.4%.

Undesirable staff turnover

The risk of losing high-performing employees raises concerns for many organisations. For example: Employee A of a sales department within any organisation is very successful and manages to retain key customers. The sales employee has a lot of product and sales knowledge, is well-liked, never ill, highly profitable and has thus developed into a key pillar within the organisation. What happens when this employee leaves the organisation? In the short term, costs arise. A new vacancy has to be put out, replacement has to be arranged, knowledge transfer, administration handling, conducting exit interview, induction process, etc. But in the above example, the biggest pain is felt mainly in the long term. The department is under pressure and similar results will not be achieved in the coming months. In the worst case, this can lead to demotivation, absenteeism and even more unwanted turnover.

In summary, in the case of unwanted turnover, the costs can be quite high, especially when one only has a short-term view. Strategic personnel management is therefore essential. HR departments should distinguish themselves in this more often by systematically providing insight into such staff turnover. Think about: Where are risks? How can we better bind and keep employees interested? What are the reasons for turnover? What can we do about it?

Desired staff turnover

As explained earlier, within desirable staff turnover, one loses employees with relatively little (tacit) knowledge. Also, the employee performs (below) average. So there is no loss of important assets or resources that add significant value to the organisation. The costs within this category are therefore mainly limited to the short term. On the contrary, in the long term gains can be made after departure.

Contrary to what some human resources officers think, knowing triggers that lead to desired employee turnover offers great profit potential. After all, organisations that do not have to cough up inflow-related costs each time are more effective.

Dealing with staff turnover

So there is a big difference between desirable and undesirable attrition. But what can we do with this distinction? And to what extent can we influence staff turnover?

First of all, only one outflow rate is often reported. No distinction is made here between desired and undesired staff turnover. Strange, because combining these categories does not really give a good picture at all. A first tip is therefore to scrutinise both the figures for desired and undesired turnover separately. This is the only way to determine whether there is either too much unwanted turnover or too little desired turnover.

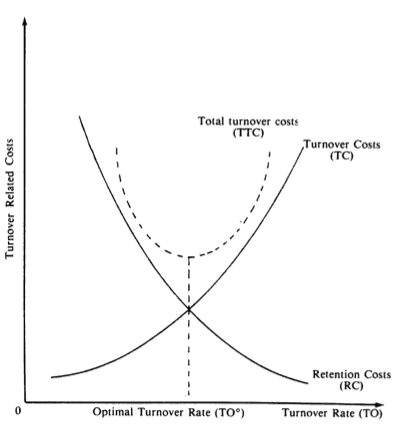

The second step is to determine the optimal attrition rate within your organisation. In some cases, an overall attrition rate of 30 per cent is nothing to worry about. At Google, for example, the average length of employment is only 1.1 years3. In other organisations, such a high attrition rate would be disastrous. So how do you know what the right attrition rate is for your organisation? As with many other things, it's all about a healthy balance sheet. However now literally, in a financial sense. This balance sheet is shown below4.

The optimal rate lies exactly at the intersection of attrition and retention costs. That sounds nice, but how can this be calculated? What exactly are attrition costs and even more difficult, what are retention costs?

Running costs

A good start is to identify costs that are objectively measurable. For example, what does putting out an ad cost? How many hours does one spend on job interviews? How much time do exit interviews cost?

Next, it is important to consider how long it takes to bring a new employee up to the level of the departed employee. If there is unwanted turnover, this will take more time than with desired turnover. What is the cost of this process? More importantly, what is the profit lost during the period when the employee is not yet at that level?

Objective retention costs

Regarding costs of retention (retention costs), things get a bit more complicated. Yet here too, there are certainly costs that can be approached objectively. In any case, step one is to understand what matters to the employee within the terms of employment when deciding whether or not to stay with the organisation. In the primary area, for example, one can look at what providing perspective/growth costs. Here, calculate the difference between the absolute starting salary and the costs required annually for an employee to achieve growth to, say, a senior role. Salary scales often help to make this explicit.

Subjective retention costs

Understanding subjective drives is trickier. How do you find out what binds employees and what makes them stay captivated? Important to find out this information is an open culture combined with a systematic feedback system. Employees must feel the space to be able to give feedback, and be given the opportunity to do so.

Giving feedback does not come naturally in every organisation. When the organisational culture is closed, the step to give feedback in an evaluation interview, for example, can be a big one. Digital, anonymous feedback solutions offer a solution here. This way, employees can offer honest and open insight into such matters. A win-win situation, as feedback solutions also contribute to creating an open culture5. Unfortunately, the question is still too often whether managers are willing, daring and able to go along with this change.

Only when a solid feedback system is in place can one really map the full scope of drivers. Only then can retention costs be further specified and the best outflow percentage determined. One can thus focus more effectively on encouraging desirable staff turnover and preventing undesirable staff turnover. Perhaps then, offering compensation for leaving the organisation is not even necessary.

Want to gain data-based insights into departure and prevention reasons? Then read here More about us (EXperience) outflow survey.

Sources

- Umoh, R. (2018). Why Amazon pays employees $5,000 to quit. CNBC.

- Johnson, J. T., Griffeth, R. W., & Griffin, M. (2000). Factors discriminating functional and dysfunctional salesforce turnover. Journal of business & industrial marketing, 15(6), 399-415.

- Johnson, T. (2018). The Real Problem With Tech Professionals: High Turnover. Forbes.

- Abelson, M. A., & Baysinger, B. D. (1984). Optimal and dysfunctional turnover: Toward an organisational level model. Academy of management Review, 9(2), 331-341.

- Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T., & Grimes, J. M. (2010). Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: E-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies. Government information quarterly, 27(3), 264-271.